Exploring Beijing Hutongs —— History, Architecture, and Siheyuan Residences

The word Hutong has been used in Beijing for more than 800 years. Its name comes from the Mongolian word for “water well.” When the Mongols established their capital in Beijing during the Yuan Dynasty, they dug wells at the entrances of alleys for daily use, which also carried meanings of Feng Shui. Because Beijing had abundant water resources, the word gradually evolved from meaning “well” to describing the passageways between houses, and has been used since the Yuan Dynasty.

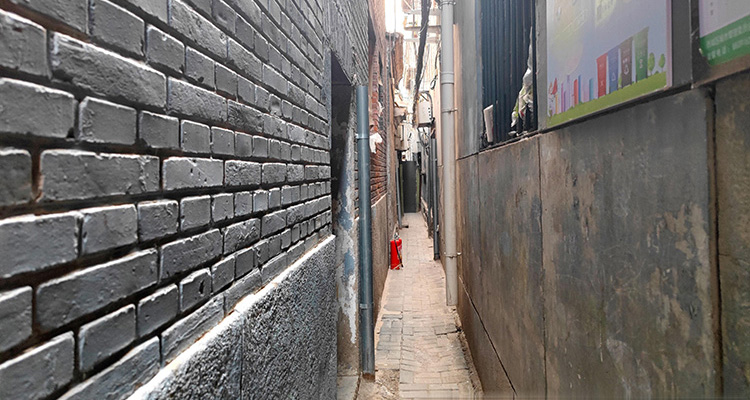

According to tradition, alleys running east–west in Beijing were called Hutongs, while those running north–south were Streets (Dajie). Alleys about 3 meters wide were Hutongs, those wider than 6 meters were called streets, and narrower ones were called Lanes (Xiang). Besides being pathways, Hutongs also served as firebreaks. Since Beijing was a planned city, the layout of Hutongs was designed with disaster prevention and evacuation in mind.

If explaining to children, you might say: 600 years ago, Mongols who settled in Beijing paid attention to Feng Shui, so they first dug wells (in Mongolian, “Hutong”) at the alley entrances, then built Siheyuan (courtyard houses) around them, gradually forming the Hutong network. Some say the original width of a Hutong was 18 Mongolian steps, equal to about 9 modern steps.

The Number of Hutongs Over Time

Historically, the number of Hutongs has constantly changed. At the end of the Qing Dynasty, there were about 3,000 Hutongs. By the Republic of China period, with population growth, the number in Beiping (old Beijing) reached about 3,200. After the 1950s, urban redevelopment and the demolition of city walls led to the disappearance of many Hutongs. Today, about 1,500 remain, mainly in Dongcheng and Xicheng Districts, the traditional inner city. Fewer than 30 Hutongs exist in suburban areas like Haidian, Fengtai, and Chaoyang, which historically were rural with low population density.

“East Rich, West Noble, South Poor, North Cheap”

In the Qing Dynasty, there was a saying: “East Rich, West Noble, South Poor, North Cheap.”

- The East City, near Chaoyang Gate, was a hub for grain transport with many warehouses. The tax station at Chongwen Gate collected 70% of Beijing’s trade tax, so merchants gathered here, making the East wealthy.

- The West City was the residence of the upper Manchu banners and many royal mansions, thus it was “noble.”

- The South City, such as Tianqiao, was where poor families and laborers lived, hence “poor.”

- The “North Cheap” had two interpretations: some say it referred to the “Eight Great Hutongs,” a red-light and theater district, with socially low status; others say it reflected Han people’s disdain toward Manchu communities in the north. The meaning remains debated

Architectural Details of Hutongs

The architecture of Hutongs reflects the residents’ social identity. For example, the Men Dun (doorstone base) in front of a Siheyuan entrance came in different styles:

- Lion-shaped: exclusive to royals or government offices, rare.

- Drum-shaped: for military officials, with variations for rank.

- Box-shaped: for civil officials, merchants, or wealthy families.

Other identity markers included:

- Threshold height: 59 cm for the Forbidden City, 36 cm for princely mansions, 29 cm for first-rank officials.

- Main gate type: Grand gates for high-ranking officials, with beams reflecting status.

- Door decorations (Men Dang Hu Dui): circular for military, square for civil officials, with numbers also showing rank.

Many gates had dragon-head knockers (Pusou), symbolizing protection and warding off evil.

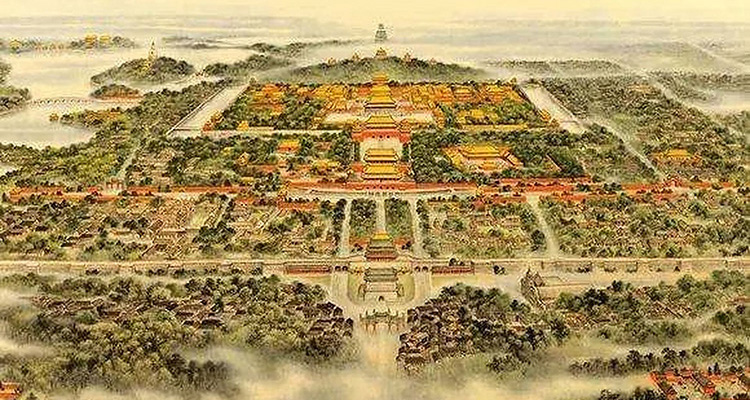

The Design of Siheyuan Courtyard Houses

The Siheyuan is one of Beijing’s oldest and most traditional residential designs. Its name comes from four houses—north main hall, south wing, east wing, and west wing—surrounding a central courtyard. The design embodies the traditional idea of harmony between heaven and earth.

- The Main Hall (north house) faced south, for elders, symbolizing authority.

- The East Wing housed sons, representing future pillars of the family.

- The West Wing housed daughters, symbolizing noble heritage.

- The South Wing was for guests or studies, symbolizing prosperity.

- The Central Courtyard symbolized earth and fertility, representing growth and wealth.

Beijing Siheyuan date back over 2,000 years, usually rectangular, longer north–south, with gates facing south. This layout aligned with Yuan Dynasty city planning and Feng Shui, and also suited Beijing’s climate—blocking cold northwest winds and allowing cool breezes from the southeast.

Different types developed, from single-entry courtyards to multi-entry compounds and garden-style residences, each reflecting Beijing’s unique style.

Famous Hutongs

- Zhuanta Hutong (Brick Pagoda Hutong): the oldest, named after a Yuan Dynasty monk’s pagoda, over 700 years old.

- Liulichang: once a tile-making kiln village, later a famous Qing Dynasty cultural street known for antiques, books, and art.

- Lingjing Hutong: the widest, up to 32.18 meters, named after the Ming Dynasty Lingji Palace.

- Qianshi Hutong: the narrowest, only 0.4 meters wide, once a coin market.

- Dongjiaominxiang: the longest, 6.5 km, once home to foreign embassies.

- Some of the shortest Hutongs measure only about 10 meters, hard to find but still part of the culture.

Conclusion

Hutongs are one of Beijing’s most important cultural symbols. Walking through them, you can feel traces of history and experience the vibrancy of local life. Together with Siheyuan courtyard houses, they form the unique charm of Beijing, blending tradition, architecture, and everyday stories into the city’s living heritage.